|

Intaglio

In

the intaglio printmaking process, lines of an image to

be printed on paper are incised first by hand-held tools

and/or acids onto the surface of (generally) a flat

metal plate, most often, copper. The surface of

the metal plate is inked and then wiped so the only ink

that remains is in the incised areas of the plate.

The paper is carefully positioned on top of the

inked metal plate and "pulled" through a press, pressure

pushing the paper onto the inked plate allowing the ink

to be transferred to the paper producing an original

print, or graphic.

With intaglio prints one can observe the outer edge of

the metal plate impressed into the paper due to the

pressure of the printing press. The paper margins

extend beyond the plate mark. Some of Picasso's

prints were printed on smaller margined papers and some

of the same image were printed on larger paper and

therefore wider margins. Engraving, drypoint,

etching, and aquatint are intaglio forms of

printmaking. Picasso is known for having extended

the boundaries and traditional means of the printmaking

techniques shown below and often combined techniques in

producing his original graphics.

Engraving

An

engraving is made by first drawing a design directly

into a metal plate using a hand-held sharp cutting

device called a burin. The burin has a sharp,

angled point at the end. The engraving technique

had been used for centuries to reproduce drawings and

paintings, a way to allow more people to own or see the

works of art by artists who would otherwise only have

the original without the possibility of additional

"copies" of the unique image. By the 19th century,

it had been largely abandoned in favor of etching.

Although Picasso's use of the burin was not always

orthodox, he and other artists would use the burin to

create sharp crisp lines on the etching plate,

translated to the same on the printed image.

Drypoint

A

drypoint (form of engraving) is made by scratching

a sharp needle into a metal plate, raising tiny ridges

that also catch ink. When the plate is printed, the

ridges produce a velvet-like burr. After a few

printings, however, the fragile burr wears out. This

technique dates back to the 15th century, and although

it is not widely used, it includes Dürer and Rembrandt

among its practitioners. Picasso used drypoint

combined with original print-making techniques, usually

to produce lines of simplicity and expressive

quality.

Etching

In

etching, a metal plate is covered with an acid-resistant

ground, usually varnish, through which the image is

drawn with a pointed tool, exposing the metal below. The

plate is then immersed in a bath of acid that bites away

the metal where it was exposed by the drawn areas that

were no longer protected by the ground. After the plate

has been "etched" and cleaned, it is ready to be inked

and printed -- or reworked by the artist. The

relatively rapid execution allowed by this technique is

the primary reason for its widespread use shortly after

its development in the 15th century. Rembrandt, in

the 17th century, created more than 300 etchings.

Picasso, in 1968, created 347 etchings for a single

suite at age 87!

Aquatint

Aquatint

is similar to etching, but uses sprinkled grains of

heated resin instead of varnish for the ground. Aquatint

creates fields of tone, not line. The "sugar-lift"

method, which Picasso employed frequently in the 347 Series, allowed

the artist to paint or draw freely and swiftly with a

brush directly on the metal plate. Aquatint was invented

in the 18th century as a variation on etching.

Sugar aquatint or

lift-ground etching was mastered by Picasso in

1936. The etching technique preserves the

artist's brushwork and permits broad areas of color

instead of just thin, dry lines.

Picasso would draw directly on the metal plate with

a black watery ink thickened by the addition of

dissolved sugar and gum Arabic. The dried

drawing is then covered with an acid-resistant

varnish or etching ground and immersed in warm

water. This penetrates the ground and

dissolves the drawing material. The plate is

lightly rubbed so that the drawing as well as the

varnish on top of it "lift off", leaving the

bare plate. The protecting vanish will still

stick to the plate where the plate has not

previously been treated with the ink and sugar

mixture.

With copper plates the direct action of the acid is

not sufficient and is too smooth, leaving gray tones

were the acid has been bitten directly into the

plate. To achieve textures like brushstrokes Picasso

would lay down an aquatint ground on the lifted

design. This resin ground now covers the bare

metal of the open lines or brush stokes lifted from

the first ground and provides well defined textures

and tones. When preparing the artwork on the

plate the artist would work spontaneously with the

pen or brush. Sugar-lift etchings are often

combined with aquatint. Picasso liked the

medium (even though it was difficult to control)

because of the variety of textures it would produce.

With an aquatint a porous ground of

acid-resistant particles is used to cover areas of

the metal plate. Heat is then used to fuse the

particles to the plate. This allows the acid

to bite away a fine grid of small dots into the

plate as when the plate is dipped in an acid bath,

the particles prevent bits of the surface from being

eaten away. The resulting dot texture creates

an illusion of tonal range that Picasso

favored.

Scraper

Picasso

often employed a scraper, an engraver's tool that

removes bits of metal, in his intaglio prints. He

modified engraved and etched lines with its triangular

edge, which he also scraped into areas of aquatint.

Sometimes he used the scraper's sharp edge to engrave

strokes that are parallel and short, or as a substitute

for a drypoint needle.

Lithograph

Lithographs

are

made by creating a drawing on a flat prepared surface,

usually a large and heavy slab of thick Bavarian

limestone. The drawing, made with a greasy crayon

or similar material, is then stabilized with a

gum-arabic solution. The plate (or flat stone)

would then be sponged with water, the greasy drawn areas

repelling the water but attracting the rolled-on ink and

the rest of the stone remaining wet and repelling the

ink. Paper is positioned over the plate, and the

pressure of the press transfers the ink from the stone

to the paper, printing a reverse image of what was

drawn. The dates in reverse in so many of

Picasso's prints is due to this fact.

Picasso

also created lithographs on zinc plates as they were

lighter and did not require him to work at the

lithographer's studio. It was 1945 that Picasso

took up residence at the Mourlot studio in Paris

enjoying the medium where he could rework an image on

the same printing surface and preserve the complete

evolution of the composition.

Picasso

later created his lithographic images on a paper which

was then transferred to the stone in reverse from the

original drawing. Then, when printed, the print

would be a reverse of the inked surface, thereby

consistent with the orientation of the original

drawing. In examples where Picasso's date is read

correctly, it is likely that the print was made by

transferring a drawing to the plate.

Linocut

Picasso's linocuts were

made by gouging out a sheet of linoleum which had been

fused onto a harder block of wood. (Linoleum,

softer and lighter than wood, allowed Picasso to work

more quickly than would have been possible by working

from woodblocks alone.) Using gouges, he would

cut out the areas of his intended image that were to

be absent of color (and therefore appear the color of

the paper when printed). The relief areas that

remain would be inked, usually with a brayer.

Paper would be put on the inked linoleum block and

pressure applied, after which the inked image is

transferred to the paper. If there were to be

multiple colors, Picasso would create a separate

linoleum block, each corresponding to a different

color, each printed in succession. This is how

he worked since his first linocuts were created in

1958.

In later years he become more economical and

ingenious, inventing the technique of printing

multiple colors from a single linoleum block by

printing the linocut, cutting out more of the block,

inking it again and printing it a second time in a

second color on the earlier printed single-color

example, successively adding colors while continuing

the process.

Steel Facing

Picasso

would

often have his etching plates steel faced.

That process involves electroplating the

already-drawn etching plate with a very thin coat of

steel to harden its surface. In doing so,

early prints would have the same quality as later

prints. Before plates were steel faced, as in

Rembrandt's time in the 17th century, the etched

lines of earlier impressions were usually blacker,

richer, and more velvety and later impressions were

grayer, flatter, and not as rich due to the lines

being worn over the course of printing an

edition. Later impressions would display a

diminishing of subtle contrasts and tonal depth from

early to later impressions.

In

this Saper Galleries exhibition are several examples

of trial and other proofs created before the etching

plates were steel faced, thereby creating richer and

more desirable impressions than those from steel

faced plates which reduce textural delicacy and

tonal depth to a degree.

|

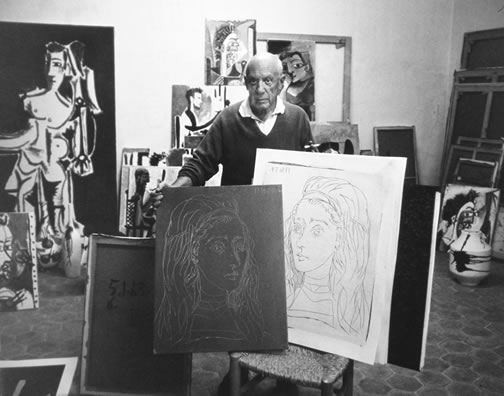

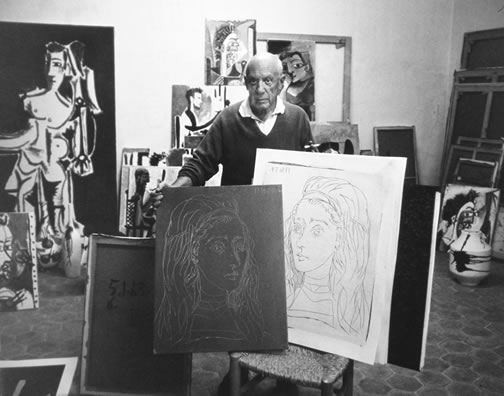

Picasso

with

linocut plate and print, 1957

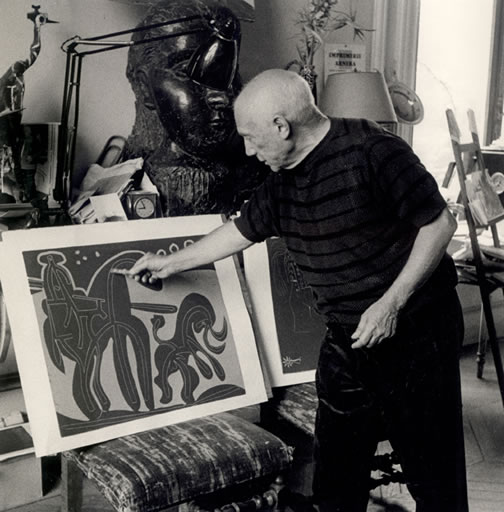

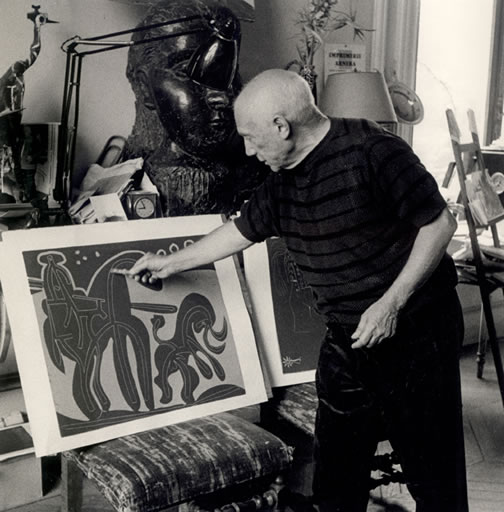

Picasso

with

linocut plate and print, 1957

Picasso

with

linocut, 1959

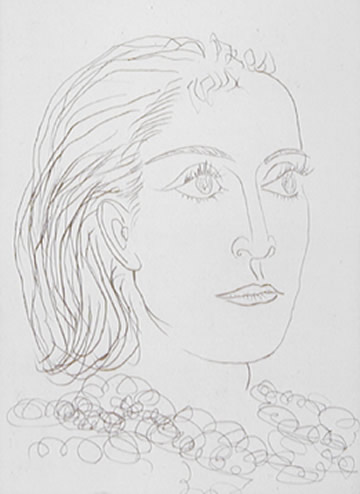

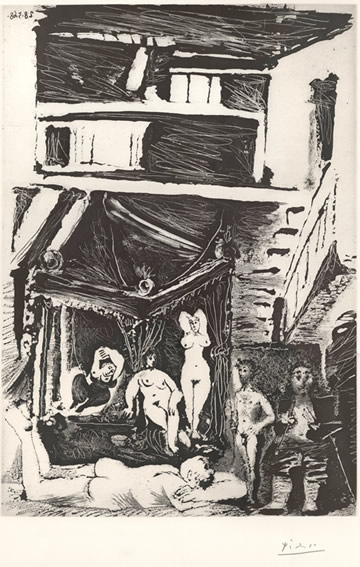

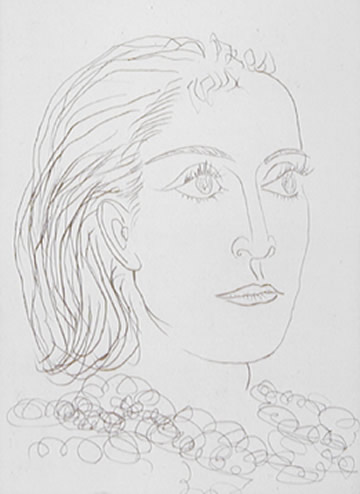

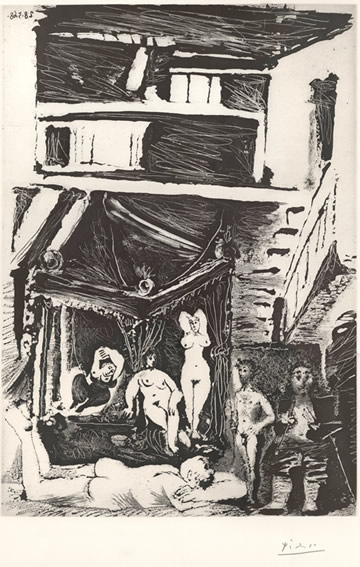

Drypoint

example,

1937

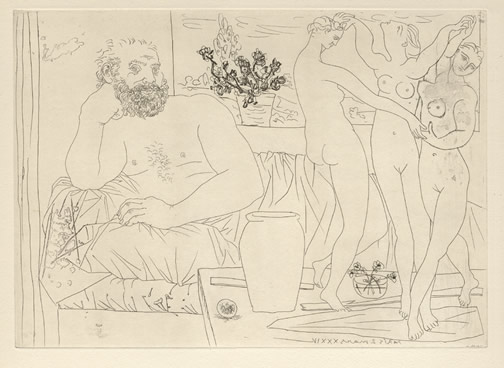

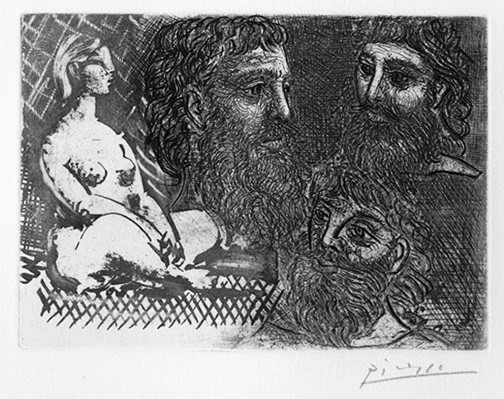

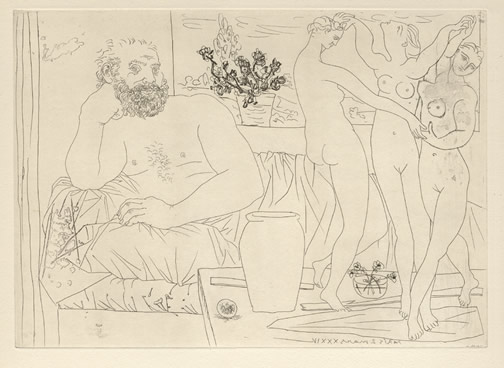

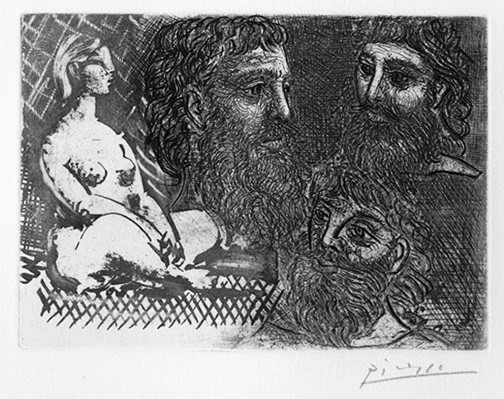

Etching

example,

1934

Sugar-lift

and

aquatint example, 1968

Sugar-lift aquatint example, 1934

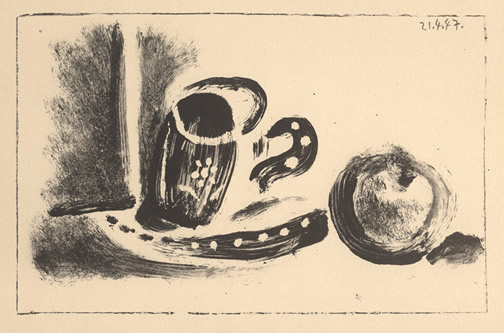

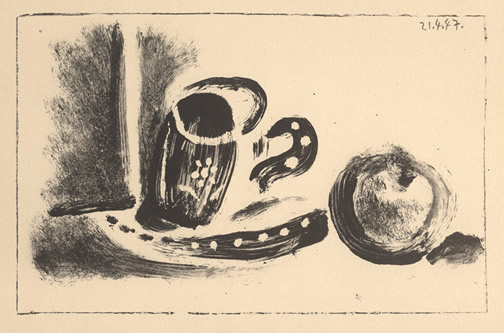

Lithograph, 1959

Lithograph transferred from drawing to stone, 1947

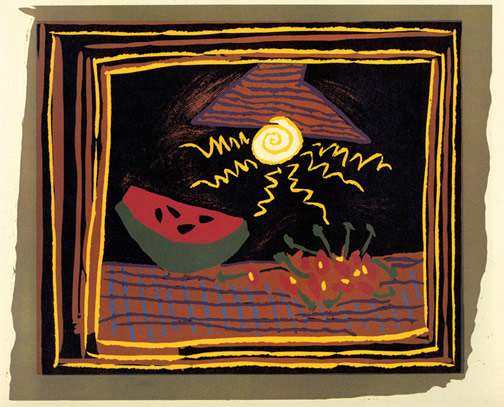

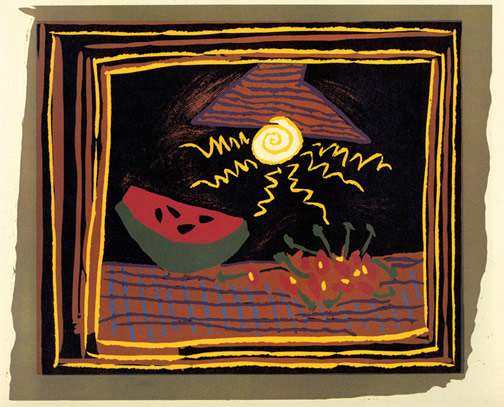

Seven-color linocut, 1962

Etching

before

steel facing, 1941-42

|